Last time, we went over the three chapters that make up Clear’s first law of behavior change: Make It Obvious. Now, we shift our focus to Clear’s second law of behavior change: Make It Attractive. This section of the book starts with Chapter 8: How to Make a Habit Irresistible.

How to Make a Habit Irresistible

Clear references a series of experiments by Dutch scientist Niko Tinbergen, who won a Nobel Prize for his work studying Herring gulls and Greylag geese raising their chicks. Tinbergen observed Herring gull chicks pecking at a red spot on adult beaks when they were hungry, which gave him an idea. He cobbled together some not-very-convincing dummy beaks on some cardboard models, and was surprised to find that the chicks would still peck at the red spot he had placed on them.

They would even peck faster when the dot was bigger, and go absolutely crazy with pecks when presented with a beak with multiple red dots. This showed that the “red-dot-pecking” behavior was hard-wired into the gull chicks’ brains and in accordance with a specific set of rules.

Tinbergen observed a similar behavior with Greylag geese that would roll eggs back into their nest if they happened to roll out, but would perform this same action with any round object that appeared to have rolled out. In one instance they even rolled a volleyball to be with their eggs, which as you’d imagine is relatively much larger.

- Scientists call this supernormal stimuli, which is essentially an exaggerated or enhanced version of a stimulus that elicits a specific behavior. Clear accurately compares this to our general cravings towards junk food: these foods are high in salt, sugar, and fat, so from an evolutionary perspective, our ancient ancestors placed a high value on these characteristics because they didn’t know when they were going to eat next. Getting food was more difficult thousands of years ago, so it would make sense to stock up on energy when it was available to you, and these cravings persist even in our now calorie-rich lifestyles.

- But where does this craving actually come from? Perhaps some of you already know, but the source is dopamine. Clear references another interesting experiment where neuroscientists blocked dopamine release in a group of rats. The rats ended up dying of thirst because they lost all desire to do . . . well, much of anything. They felt no desire for drinking, eating, mating, etc. They tried this same experiment with another group of rats, but this time they regularly provided them with sugar water, and what they found is that the rats still found the taste and act of drinking the sugar water pleasurable, but there was just no innate desire to seek it out with blocked dopamine releasers. Without desire, there was no action.

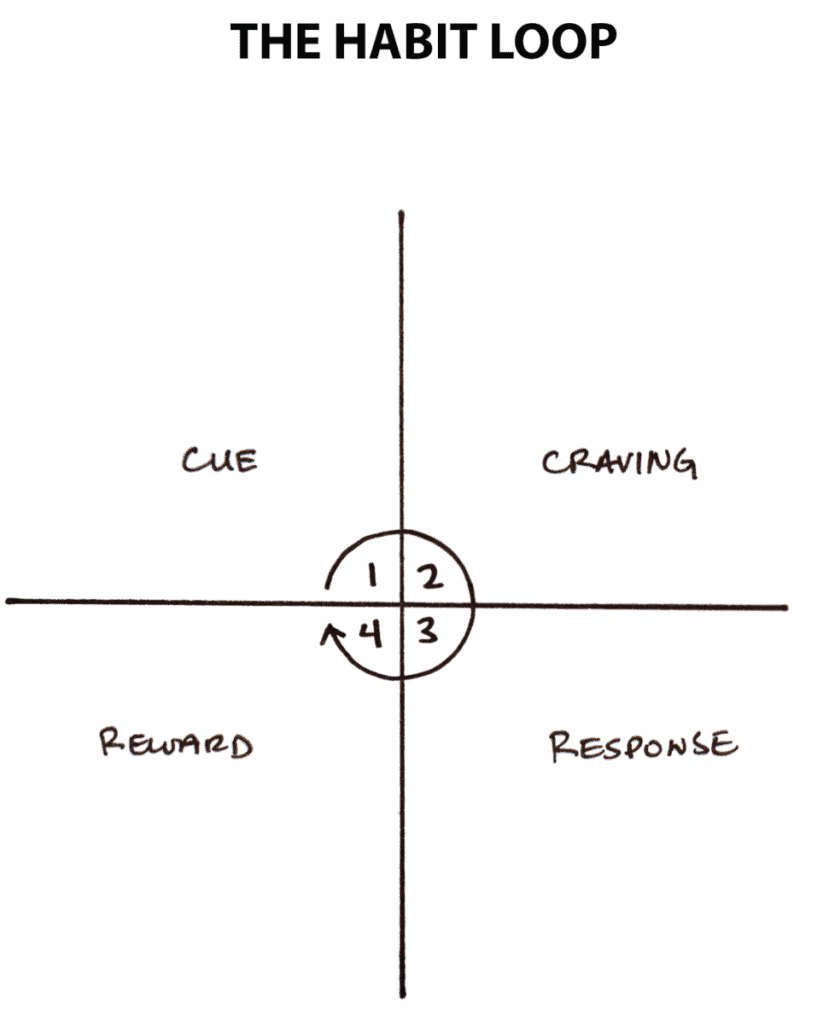

- Clear goes on for some length about dopamine, but something interesting he points out is that dopamine levels are higher during a reward phase when it is experienced for the first time, but subsequent dopamine spikes occur at the craving phase to spur action when the identified reward is once again obtainable. He uses examples of cocaine and gambling addicts and how their dopamine spikes occur upon sight of the drug and the moments before placing a bet, respectively (…obviously). Dopamine is what drives cravings and action for rewards, though it’s not all about pleasure; dopamine plays an essential role in motivation, learning, memory, punishment/aversion, and movement.

- Clear then introduces the idea of temptation bundling, in which you can manipulate these cravings to link an action you “want to do” with an action you “need to do.” This is very similar to the habit stacking strategy mentioned in Chapter 5, and is a great way to start and maintain good habits if they’re associated with an already-established reward.

Image credit to James Clear

Personally, I liked the experiments mentioned in this chapter, and I felt like I learned a lot more about dopamine, i.e. I didn’t realize how crucial it was for action, and was also surprised to learn that the dopamine levels are higher during cravings rather than rewards since it’s so popularly associated with pleasure. The temptation bundling was interesting, but to be honest I thought it was pretty much the same as habit stacking, though maybe I’m missing something here that sets it apart.

The Role of Family and Friends in Shaping Your Habits

We’ve arrived at Chapter 9: The Role of Family and Friends in Shaping Your Habits

Clear begins this chapter with the story of Laszlo Polgar, and how he courted his wife-to-be Klara with the idea of… well, raising “super children.” Apparently, his mantra was “A genius is not born, but is educated and trained,” and though Klara may not have been as zealous as Laszlo in this pursuit, she generally agreed with this idea and ended up marrying and having children with Laszlo.

Laszlo chose chess as the activity he wanted his children to become geniuses in, and thus he created an environment rich with chess-related activities in which to raise them. Their household was filled with chess books, pictures of famous chess players, various opportunities for their children to play chess against one another, etc. This was all planned before their kids were even born, and when they were, they grew passionate about chess and became prodigies just as Laszlo had predicted.

All three of their daughters went on to earn impressive accolades in the chess world; Susan, their eldest daughter, was beating adults when she was four years old, and Judit, their youngest, became the top-ranked female chess player in the world for 27 years.

- This story is a good segue into the theme of the chapter; how habits are influenced and formed by social norms, whether it’s by family, friends, a random crowd, etc. Clear lists out the three groups that have the greatest influence on the habits we imitate: the close, the many, and the powerful.

- Imitating the habits of the close is a concept we’re pretty familiar with at this point, though this time around Clear focuses on the social environment rather than the physical one. People copy the habits of the people they’re around, and Clear gives personal examples of how he’ll copy the body posture of someone he’s talking to without noticing or unintentionally imitate local accents when traveling in another country. He makes the point that, if you surround yourself with the social culture for habits you want to maintain, you’re much more likely to maintain them (e.g. hanging out with fit friends on a regular basis to encourage exercise and other healthy habits).

- Clear references a series of experiments conducted by Solomon Asch to demonstrate how people will mimic the habits of the many. Subjects were shown one card with a line on it, then presented with a second card with multiple lines to choose from. Subjects simply had to choose the line on the second card that was the same length as the line on the first. However, subjects were presented these cards with a group of actors, playing the roles of other subjects who were actually in on the experiment. When presented with the second card, the actors would choose and agree on an obviously incorrect line option, and the real subject would change their answer to go along with the crowd a whopping 75% of the time.

- The last group we tend to copy the habits of are that of the powerful. Clear generally refers to perceptions of power, prestige, and status, and how people are likely to mimic the habits of people they perceive as having these qualities. The reason we copy the habits of successful people is because, well, we ultimately desire success ourselves.

This chapter comes highly recommended from me, as it’s filled with many real-world examples that make it easier to read through and gives strong, legitimate support to the ideas Clear presents here. I think mimicking the habits of the close and the many makes a lot of sense to me; I find myself copying the tonations of the way my parents speak to this day, and I have also been guilty of copying accents if I am around them on a regular basis.

Not sure if I completely agree on copying the habits of the powerful; I feel like these habits may be more variable from person-to-person, as people perceive “power” in different ways. Someone might perceive the top player in the world for a particular esport as powerful or influential in some way, and want to copy the gaming habits of this person (…likely not healthy), while others may raise an eyebrow and say “What? They’re just video games. Why would anyone care about that guy?” Some people may even avoid connecting or being influenced by anyone they perceive in a position of power.

Again, this chapter focuses on our environment and how we can manipulate it to influence good habits like previous ones, but this time around it’s more about the people in this environment, and who we choose to surround ourselves with to encourage and create these good habits. Has anyone here ever joined a group of people/community to start a good habit, or conversely left a group to get rid of an undesirable one?

How to Find and Fix the Causes of Your Bad Habits

Now we look at Chapter 10: How to Find and Fix the Causes of Your Bad Habits.

This chapter treads familiar territory with a focus on cues and their associated behaviors. However, instead of opening the chapter with a study or experiment, Clear offers a personal experience which involves a friend of his, Mike, who was able to drop the bad habit of smoking over a pack a day. Mike says he picked up the habit because of his friends, but was able to drop the habit easily after reading the book Allen Carr’s Easy Way to Stop Smoking. Clear was never a smoker but read the book out of pure curiosity, and discovered that it was filled with providing different ways to look at common smoking cues. Some of the things Carr says are:

- “You think you are quitting something, but you’re not quitting anything because cigarettes do nothing for you.”

- “You think smoking is something you need to do to be social, but it’s not. You can be social without smoking at all.”

- “You think smoking is about relieving stress, but it’s not. Smoking does not relieve your nerves, it destroys them.”

The rest of the book is filled with similar literal barrages to make the reader realize smoking does nothing for them, and there are so many positives to gain by quitting. By the end of the book, smoking seems so illogical that it’s very easy for the reader to quit.

- From here, Clear expands upon the nature of cravings and how they are tied to some pretty basic human appetites. For instance, wanting to eat a bag of Cheetos doesn’t arise from a specific craving of Cheetos, it is just a specific manifestation of something more evolutionary, like obtaining food and water or perhaps building up and conserving energy. The human brain did not evolve to desire things like cigarettes or video games; their motivators are more deeply rooted and less specific.

- Clear says habits are all about their associations. Environmental cues, like seeing a red glow on an electric stovetop, makes your brain run a simulation to predict the best course of action in a given moment, like avoiding to touch said stovetop because it’s likely you could get burned.

- With this awareness, Clear suggests that we can manipulate our associations with these cues to influence our behaviors and habits. He provides a strategy of changing the language of your thoughts to be more positive, e.g. instead of saying “I have to wake up early for work” or “I have to cook dinner for my family” you can try saying “I get to wake up early for work” or “I get to cook dinner for my family.” Sometimes this small but positive twist can spur action in the right direction.

- Clear offers other association-manipulating strategies throughout the second half of the chapter with good examples, like his pre-game stretching ritual before baseball games and how, no matter what mood he was in, this sequence would always put him in the right mindset for a baseball game. He also mentions Ed Latimore, a boxer/writer who listened to music to increase his focus, but ultimately came to the realization that the act of putting on headphones was enough to get into the same focused mindset, even without the music playing.

For my thoughts, I liked the majority of this chapter; I think it promotes self-awareness for the source of bad behaviors that are difficult to identify. Or, perhaps, we purposefully avoid confrontation with these bad habits since we want to avoid discomfort, and the chapter tells us to stop kidding ourselves.

I think all the strategies in this chapter are pretty grounded in reality and will likely have measurable effects, but the “changing of the language” bit doesn’t resonate as strongly with me. This might just be me, but I need a little more of a kick to spur me into changing my behaviors/habits than switching the words “have” to “get to” in my daily planning, which don’t even sound all that “positive” to me half the time. But again, I acknowledge that it’s perhaps just a strategy that isn’t effective for me personally, and could be the way to go for someone else trying to view the world less like a pessimist.

We’ll be back next time with a look at the third law of behavior change: Make It Easy.